What Is Value Investing?

Value investing is an investment approach that involves identifying and purchasing securities—primarily stocks—that appear to be trading for less than their intrinsic or fundamental value. Practitioners aim to buy these assets at a discount, providing a “margin of safety” against potential errors in analysis or market downturns. Over time, as the market recognizes the true value, the price is expected to rise toward that intrinsic level. This article is not financial advice or trade advice, only an explanation.

The core philosophy treats stocks as partial ownership in businesses rather than mere ticker symbols. Investors focus on underlying business quality, earnings, assets, and cash flows, rather than short-term price fluctuations or market sentiment.

While variations exist, value investing traces its modern roots to systematic frameworks developed in the early 20th century. Below, we explore the primary definitions and their historical evolution.

The Foundational Definition: Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (1930s–1940s)

Value investing as a formalized discipline originated with Benjamin Graham and David Dodd at Columbia Business School.

In 1934, they published Security Analysis, a comprehensive textbook emphasizing rigorous fundamental analysis of financial statements to determine a security’s intrinsic value. Graham, often called the “father of value investing,” refined these ideas in his 1949 book The Intelligent Investor, which introduced the famous “Mr. Market” allegory: the market as a manic-depressive partner offering daily prices that investors can choose to accept or ignore.

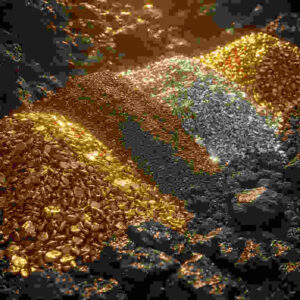

Graham’s definition focused on quantitative metrics: buying stocks trading below net current asset value (NCAV, or “net-nets”—assets minus all liabilities), low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, or low price-to-book (P/B) values. The “margin of safety”—purchasing at a substantial discount to conservatively estimated value—was central to protect against downside risk.

This version emerged post-1929 Crash, where Graham lost heavily but recovered by applying disciplined analysis. It appealed during the Great Depression, emphasizing defense over speculation.

The Evolution: Warren Buffett and Quality Focus (1950s–Present)

Warren Buffett, Graham’s student and employee at Graham-Newman Corporation in the 1950s, popularized and adapted the approach.

Buffett initially followed pure Graham-style “cigar butt” investing—buying mediocre companies at deep discounts for one last “puff” of value. Influenced by partner Charlie Munger in the 1970s, he shifted toward “wonderful companies at fair prices” rather than “fair companies at wonderful prices.”

Buffett’s definition retains the margin of safety but incorporates qualitative factors: economic moats (sustainable competitive advantages), strong management, predictable earnings, and long-term growth potential. He views stocks as businesses, holding indefinitely if fundamentals remain sound.

This evolution addressed Graham’s quantitative limits in a changing market—fewer “net-nets” post-WWII prosperity. Buffett’s success through Berkshire Hathaway demonstrated the approach’s adaptability, blending Graham’s discipline with growth-oriented assessment.

Modern Interpretations and Variations (Late 20th–21st Century)

Value investing has spawned sub-schools:

- Deep Value: Adherents like Walter Schloss or Seth Klarman stick closely to Graham’s quantitative bargains, often in distressed or overlooked securities.

- Activist Value: Investors like Carl Icahn or Bill Ackman buy undervalued stocks and push management for changes (e.g., spin-offs, buybacks) to unlock value.

- Global and ESG-Infused Value: Contemporary practitioners incorporate international markets or environmental/social factors while maintaining core undervaluation principles.

Studies and investor letters (e.g., Buffett’s annual Berkshire reports) show value strategies have historically outperformed in certain periods, though they’ve faced challenges in growth-dominated markets like the 2010s.

Core Principles Across Definitions

Despite variations, common threads include:

- Intrinsic value calculation via fundamentals (earnings, assets, dividends).

- Margin of safety to buffer against uncertainty.

- Long-term horizon, ignoring short-term volatility.

- Discipline and contrarian mindset—buying when others are fearful.

Value investing contrasts with growth investing (betting on high-future-earnings companies at premium prices) or momentum trading (following trends).

From Graham’s Depression-era conservatism to Buffett’s quality emphasis, value investing remains a disciplined framework for approaching markets as business ownership rather than speculation. Its history reflects adaptation to economic shifts while preserving the focus on buying assets below their worth.

2 comments