What is Asset Allocation?

This article is not financial advice or trade advice, only an explanation.

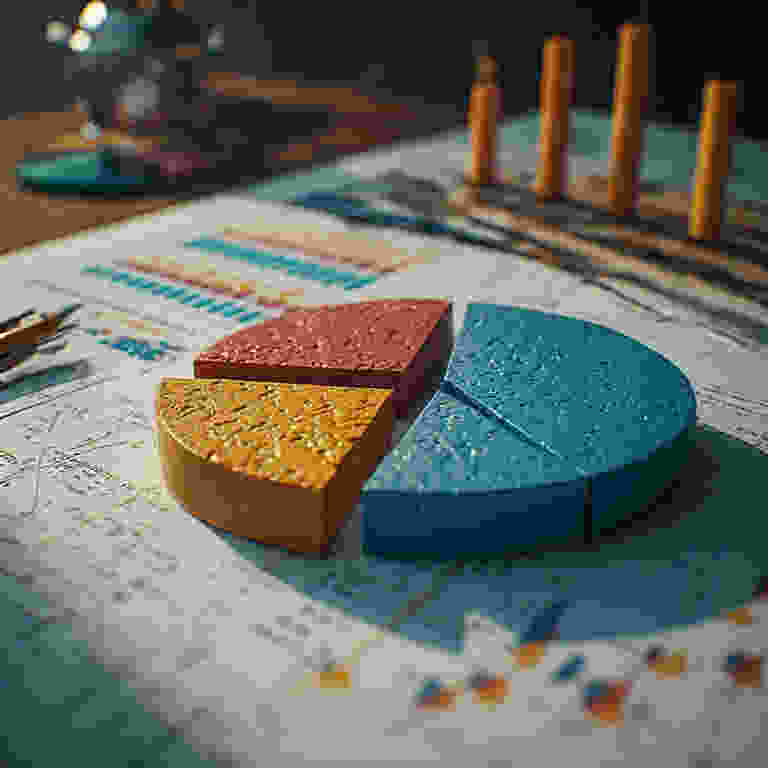

Asset Allocation is The Architecture of an Investment Portfolio? Asset allocation is a fundamental investment principle that involves dividing an investment portfolio among different asset categories, such as stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities. It is not a strategy for picking individual securities, but rather a high-level framework for determining what percentage of a portfolio should be exposed to different types of assets. The central premise is that different asset classes have different risk and return characteristics and perform differently under varying economic conditions. The primary goal of asset allocation is to create a mix of assets that aligns with an investor’s specific goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon, with the aim of managing overall portfolio risk.

Part 1: The Theoretical Foundation

The modern concept of asset allocation is rooted in academic finance, notably Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), introduced by Harry Markowitz in the 1950s. MPT argues that an investor can construct an “efficient frontier” of optimal portfolios offering the maximum possible expected return for a given level of risk. The key insight is that the risk of a portfolio is not simply the sum of the risks of its individual assets, but depends on how those assets’ prices move in relation to one another—a concept known as correlation.

- Diversification: This is the practical outcome of applying MPT. By combining asset classes with low or negative correlations (meaning they do not all move up and down at the same time or to the same degree), the overall volatility (risk) of the portfolio can potentially be reduced without necessarily sacrificing expected return. A decline in one asset class may be offset by stability or gains in another.

Part 2: The Primary Asset Classes

A basic asset allocation model typically considers three core categories, each with distinct characteristics:

- Equities (Stocks): Represent ownership shares in publicly traded companies.

- General Risk/Return Profile: Historically, higher potential for long-term growth (return) coupled with higher short-term price volatility (risk).

- Sub-Classes: Can be further divided by company size (large-cap, small-cap), geography (domestic, international, emerging markets), or sector (technology, healthcare, energy).

- Fixed Income (Bonds): Represent loans made to governments or corporations in exchange for periodic interest payments and the return of principal at maturity.

- General Risk/Return Profile: Generally lower long-term return potential than stocks, but also typically lower volatility. Often used to provide income and stability to a portfolio.

- Cash and Cash Equivalents: Includes physical currency, savings accounts, money market funds, and short-term Treasury bills.

- General Risk/Return Profile: Lowest return potential, but also the lowest risk of principal loss and the highest liquidity (ease of conversion to cash).

Additional asset classes often incorporated into more complex allocations include:

- Real Assets: Real estate (physical or through REITs), infrastructure, and commodities (like gold, oil, timber).

- Alternative Investments: Hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, and cryptocurrencies. These often have different return drivers and liquidity profiles compared to traditional stocks and bonds.

Part 3: The Determinants of an Allocation Strategy

An appropriate asset allocation is not universal; it is personalized based on several key factors:

- Investment Goals: What is the capital intended to fund? (e.g., retirement in 30 years, a home down payment in 5 years, generating stable income now).

- Time Horizon: The length of time an investor expects to hold the investment before needing to access the capital. A longer horizon generally allows for a greater allocation to more volatile assets like stocks, as there is more time to recover from market downturns.

- Risk Tolerance: An investor’s psychological and financial ability to endure fluctuations in the value of their portfolio. This is subjective and involves understanding how one might react emotionally to significant market declines.

These factors are often summarized in investor “profiles,” such as Conservative, Moderate (or Balanced), and Growth (or Aggressive).

Part 4: Illustrative Examples of Allocation Models

The following are simplified, hypothetical examples to illustrate how asset allocation might differ based on investor profiles. They are for educational purposes only.

Example 1: A Conservative Allocation for a Near-Term Goal

- Scenario: An individual saving for a home down payment they plan to use in 2-3 years. Their primary objective is preservation of the accumulated capital.

- Potential Allocation:

- 40% Short-to-Intermediate Term Bonds

- 50% Cash and Money Market Funds

- 10% Diversified Stocks (for modest potential growth)

- Rationale: The high allocation to cash and bonds prioritizes low volatility and liquidity, reducing the risk of a market downturn significantly eroding the savings right before the funds are needed.

Example 2: A Moderate/Balanced Allocation for a Mid-Term Goal

- Scenario: An investor with a 10-year time horizon, perhaps for a child’s future education expenses, with a moderate comfort level with market fluctuations.

- Potential Allocation (a classic “60/40” portfolio):

- 60% Diversified Stocks (mix of domestic and international)

- 40% Diversified Bonds (mix of government and high-quality corporate)

- Rationale: This seeks a balance, using stocks for growth potential to outpace inflation over the medium term, while the bond component aims to provide income and cushion against some of the volatility of the stock market.

Example 3: A Growth-Oriented Allocation for a Long-Term Goal

- Scenario: A young professional saving for retirement in 30+ years. They have a long time horizon and a high tolerance for risk, as they will not need the funds for decades.

- Potential Allocation:

- 80% Diversified Stocks (with a tilt toward growth-oriented sectors and international/emerging markets)

- 15% Diversified Bonds

- 5% Real Assets (e.g., a REIT fund)

- Rationale: The heavy emphasis on stocks is designed to maximize long-term growth potential. The investor can theoretically withstand significant short-term market cycles with the expectation of higher returns over the full period.

Part 5: Strategic vs. Tactical Asset Allocation

- Strategic Asset Allocation: This is the long-term, policy portfolio mix based on the investor’s goals, horizon, and risk tolerance. It serves as a permanent baseline. Periodic rebalancing is required to return the portfolio to its original target percentages after market movements alter them. This forces a discipline of “selling high” (assets that have grown above their target) and “buying low” (assets that have fallen below their target).

- Tactical Asset Allocation: This involves making short- to medium-term adjustments to the strategic allocation to capitalize on perceived market opportunities or risks. For example, a manager might temporarily overweight a specific sector they believe is undervalued. This is a more active approach and differs from the set-and-forget nature of a pure strategic allocation.

Conclusion: The Foundational Discipline

Asset allocation is widely regarded by financial academics and practitioners as one of the most critical decisions in the investment process. Research suggests that over time, a portfolio’s long-term risk and return characteristics are influenced more by its asset allocation than by individual security selection or market timing.

It may provides a structured, disciplined framework for building a diversified portfolio that systematically addresses an investor’s unique financial situation. By explicitly defining the role of different asset classes, it establishes a rational plan for pursuing financial goals while managing the inherent uncertainty of financial markets.

2 comments