Recession: The Economic Contraction and Its Market-Wide Reverberations

A recession is a significant, widespread, and prolonged downturn in economic activity. While often simplistically defined as two consecutive quarters of decline in a country’s real (inflation-adjusted) Gross Domestic Product (GDP), official bodies like the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) use a broader definition. They consider a recession to be a “significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.” Recessions are a natural, albeit painful, phase of the business cycle, following periods of expansion and preceding recoveries. This article examines the characteristics of a recession and explores its multifaceted, non-prescriptive effects across stock markets, foreign exchange (forex) markets, and other major financial asset classes.

This article is not financial advice of any kind. and does not predict anything in the future.

Part 1: Defining and Identifying a Recession

1.1 Beyond the GDP Rule of Thumb

The “two-quarter” rule is a useful heuristic but not a formal criterion. The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee, the official arbiter for the U.S., looks at a coincident constellation of indicators:

- Real Personal Income less Transfers

- Nonfarm Payroll Employment

- Real Personal Consumption Expenditures

- Wholesale-Retail Sales adjusted for inflation

- Industrial Production

A recession is marked by a broad-based deterioration across these metrics, not just in output.

1.2 Causes and Catalysts

Recessions can be triggered by various events that collapse aggregate demand or disrupt supply:

- Financial Crises: Credit crunches and banking failures (2008 Global Financial Crisis).

- External Shocks: Sudden commodity price spikes (1970s oil shocks) or global pandemics (COVID-19, though its recession was uniquely sharp and brief).

- Tight Monetary Policy: Central banks raising interest rates aggressively to combat inflation, which can slow demand to the point of contraction.

- Bursting of Asset Bubbles: The collapse of overvalued stock or housing markets.

- Loss of Confidence: A sharp decline in business and consumer sentiment, leading to reduced investment and spending.

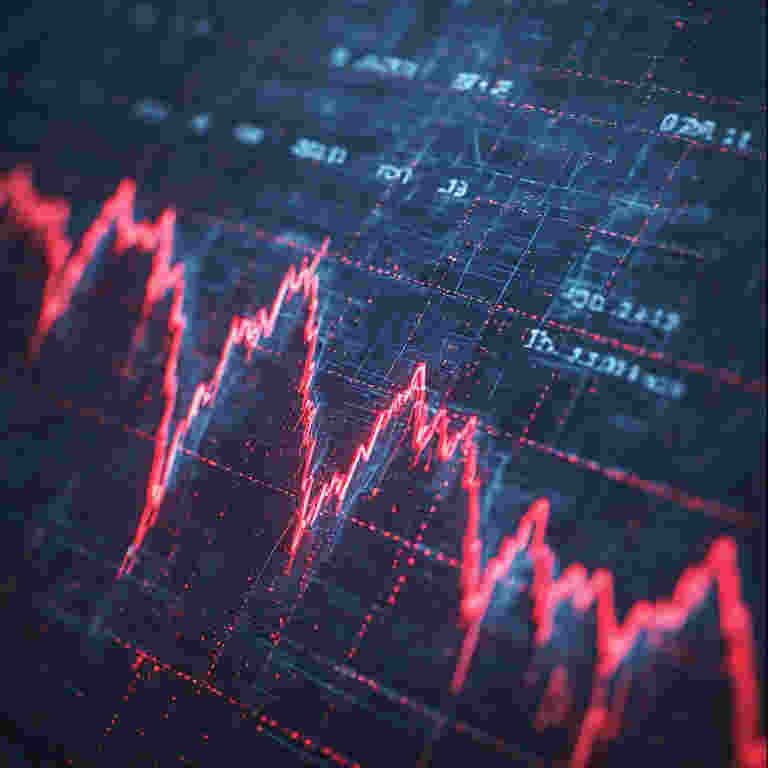

Part 2: The Transmission to Stock Markets

Equity markets are forward-looking discounting mechanisms. Their reaction is often anticipatory and pronounced.

1. The Earnings Contraction Channel: A recession implies declining economic activity, which directly translates into lower corporate revenues and profits. Analysts downgrade future earnings estimates en masse. Since stock prices reflect the present value of future earnings, this exerts powerful downward pressure on valuations. Cyclical sectors (e.g., consumer discretionary, industrials, materials, financials) typically suffer the most severe earnings declines, while defensive sectors (e.g., utilities, consumer staples, healthcare) show relative resilience.

2. The Multiple Compression Channel: In a recession, uncertainty and risk aversion rise. Investors demand a higher risk premium, which increases the equity risk premium (ERP) and, by extension, the discount rate used to value future earnings. This compression of price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples can cause stock prices to fall even if earnings expectations hold steady. The “flight to quality” can also depress multiples broadly.

3. Liquidity and Sentiment Deterioration: As losses mount, leveraged investors may face margin calls, forcing indiscriminate selling. Retail investors may panic and exit the market. This can lead to capitulation—a final, violent sell-off marked by high volume and extreme fear, often seen as a potential bottoming signal.

4. The Counter-Intuitive Rally: Stock markets typically bottom 4-6 months before the recession ends and begin recovering while economic data is still bleak. This is because they anticipate the eventual policy response (e.g., central bank easing) and the future earnings recovery. The worst time for stocks is often the late stages of an economic expansion and the very beginning of a recession.

Part 3: The Transmission to Forex (Foreign Exchange) Markets

Currency reactions in a recession are more nuanced and depend critically on relative performance and monetary policy expectations.

1. The Safe-Haven Flow (The Dominant Initial Force): In a global recession or crisis, capital seeks safety and liquidity. This typically benefits traditional safe-haven currencies:

- U.S. Dollar (USD): Strengthens due to the depth of U.S. Treasury markets, global demand for dollar liquidity, and its status as the world’s primary reserve currency.

- Japanese Yen (JPY): Strengthens due to Japan’s net creditor status, leading to repatriation of overseas investments.

- Swiss Franc (CHF): Strengthens due to Switzerland’s historical neutrality, political stability, and strong external balance sheet.

2. The Growth and Interest Rate Differential Channel:

- Domestic Recession with Global Growth: If Country A enters a recession while its major trading partners (Country B) remain healthy, Country A’s central bank is likely to cut interest rates relative to Country B’s bank. This narrowing interest rate differential can lead to capital outflows from Country A’s currency to Country B’s, weakening Currency A.

- Synchronized Global Recession: In this scenario, the focus shifts to which central bank will cut rates more or less aggressively and which economy is perceived as more resilient. The currency of the economy seen as having the strongest fundamentals or the most hawkish central bank (slowest to ease) may outperform.

3. The Commodity Currency Vulnerability: Currencies of nations reliant on commodity exports (e.g., Australian Dollar – AUD, Canadian Dollar – CAD, Norwegian Krone – NOK) are particularly sensitive to recessions, as global economic contraction crushes demand for raw materials (oil, copper, iron ore), driving down their terms of trade and currency values.

4. Policy Response is Paramount: A currency’s path depends heavily on the government’s and central bank’s response. Aggressive fiscal stimulus may support a currency by boosting growth prospects, or weaken it by raising debt sustainability concerns. Unconventional monetary policy (quantitative easing) is typically seen as negative for a currency, as it increases its supply.

Part 4: Effects on Other Major Markets

1. Fixed Income (Bond Markets):

- Government Bonds: Typically rally strongly (yields fall) during recessions. As growth slows and inflation fears recede, central banks cut policy rates. Furthermore, the “flight to safety” boosts demand for sovereign debt, especially from creditworthy governments (U.S., Germany). The yield curve often steepens initially as short-term rates fall faster than long-term rates.

- Corporate Bonds: Performance diverges sharply by credit quality. Investment-grade bonds may benefit from falling risk-free rates, though spreads may widen. High-yield (junk) bonds face severe stress as default risks skyrocket, leading to massive spread-widening and price declines, correlating more closely with equities.

2. Commodity Markets:

- Industrial Commodities (Oil, Copper, Aluminum): Demand is highly pro-cyclical. Recessions lead to collapsing industrial production and construction, causing sharp price declines in these “growth-sensitive” commodities.

- Precious Metals (Gold): Behavior is complex. Gold can initially be sold during a severe liquidity crunch (as in March 2020) as investors raise cash. However, if the recession leads to massive monetary easing and currency debasement concerns, gold often rallies strongly as a perceived store of value and hedge against future inflation.

- Agricultural Commodities: More insulated but still affected by reduced demand and lower input costs (energy, fertilizer). Prices are more driven by specific supply (weather) factors.

3. Real Estate:

- Commercial Real Estate (CRE): Vacancy rates rise as businesses fail or contract. Rental income falls, and property values decline. Financing becomes difficult.

- Residential Real Estate: Typically sees a slowdown in transactions and price declines as unemployment rises, consumer confidence falls, and credit tightens. The severity depends on pre-recession leverage and speculation levels.

Conclusion: A Recalibration of Risk and Value

A recession acts as a brutal but effective mechanism for repricing risk and clearing excesses built up during the preceding economic expansion. Its effects are not uniform but propagate through interconnected channels of earnings, monetary policy, and investor psychology.

For stock markets, it is a period of valuation reset and leadership change. For forex markets, it is a test of relative economic strength and policy credibility, driving capital to perceived safe harbors. For bonds, it creates a bifurcation between safe sovereigns and risky credit. For commodities, it separates essential needs from discretionary industrial demand.

The critical takeaway is that markets are anticipatory. The most severe price adjustments often occur in anticipation of the recession or in its early stages, not during its deepest trough. Furthermore, the policy response—the scale and speed of fiscal and monetary intervention—has become a dominant variable in determining the depth of the market downturn and the shape of the eventual recovery. Understanding these dynamics provides a framework for interpreting market behavior during economic contraction, not as random noise, but as a logical, if painful, repricing of assets in a suddenly risk-averse world.

2 comments