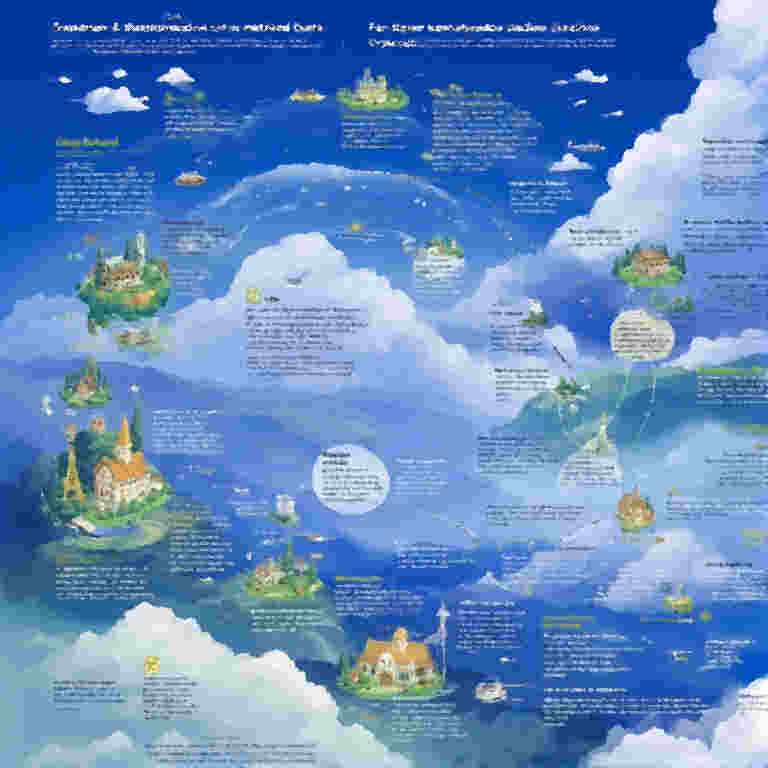

Interest Rate and Central Bank Policy Cycles: The Macroeconomic Pendulum

Interest rate cycles and Central Bank policy cycles represent the rhythmic, long-term fluctuations in the cost of borrowing and the strategic stance of monetary authorities. They are not random events but systematic responses to the oscillations of the broader economy between expansion and contraction. These cycles dictate the price of money across time horizons and are among the most powerful forces shaping the environment for all financial assets. This article explains the nature of these interconnected cycles and their established transmission mechanisms to stock and foreign exchange markets. This article is not financial advice or prediction of any asset but for common knowledge only.

Part 1: Defining the Cycles

1.1 The Interest Rate Cycle

The interest rate cycle refers to the long-term pattern of rising and falling interest rates across the economy. It is an outcome or a manifestation driven by underlying economic forces and central bank policy. The cycle typically mirrors, with a lag, the business cycle (periods of economic expansion and recession).

- Phase 1: Rising Rates (Tightening Cycle): Occurs during periods of strong economic growth, rising asset prices, and, crucially, increasing inflation. Interest rates rise as demand for credit increases and central banks act to cool the economy.

- Phase 2: Peak Rates: The point where interest rates reach their highest level in the cycle, often coinciding with late-stage economic expansion or the early onset of an economic slowdown.

- Phase 3: Falling Rates (Easing Cycle): Occurs as economic growth slows or contracts, unemployment rises, and inflationary pressures subside. Central banks cut rates to stimulate borrowing and investment.

- Phase 4: Trough Rates: The point where interest rates reach their lowest level, often maintained during a recession or the early stages of a fragile recovery.

1.2 The Central Bank Policy Cycle

This is the deliberate, strategic process followed by monetary authorities (like the Federal Reserve, ECB, or Bank of England) to manage the interest rate cycle and achieve their statutory mandates, typically price stability and maximum employment.

The cycle follows a structured sequence of phases:

- Data-Dependent Monitoring: Continuous assessment of inflation (CPI, PCE), employment (unemployment rate, wage growth), and GDP growth data.

- Forward Guidance: Communication to the public about the likely future path of policy based on the economic outlook.

- Policy Shift Initiation: The decision to begin a series of interest rate hikes (a tightening cycle) or cuts (an easing cycle).

- Execution & Calibration: Implementing rate changes at regular meetings, with the pace and magnitude (“25 vs. 50 basis points”) calibrated to incoming data.

- Pause & Assessment: Halting rate changes to observe the lagged effects of previous policy actions on the economy.

- Pivot: The critical shift from one policy direction to another (e.g., from hiking to cutting).

This policy cycle is proactive, forward-looking, and aims to smooth the extremes of the business cycle.

1.3 Special Case of Islamic Finance

Some economy style such as Islamic Finance prohibit interest. But even without interest rates, Islamic finance still reacts to economic cycles, but differently:

- Benchmarking to conventional rates: In practice, many Islamic banks use conventional benchmarks (like LIBOR or SOFR) to price contracts for competitiveness. This means Islamic finance indirectly feels the effects of interest rate cycles, though not through direct interest charges.

- Asset-linked returns: Profit margins in Murabaha or rental rates in Ijara may adjust based on market conditions, but they are tied to real assets or trade values, not abstract interest rates.

- Liquidity management: Islamic banks use Shari’ah-compliant instruments (like Sukuk) to manage liquidity. Their yields are structured around asset performance rather than central bank interest cycles.

Part 2: The Transmission to Equity Markets

Central bank policy cycles affect stock valuations through multiple, sometimes competing, channels.

During a Tightening Cycle (Rising Rates):

- Valuation Pressure: Higher risk-free rates (e.g., Treasury yields) increase the discount rate used in equity valuation models, applying downward pressure on the present value of future earnings. This disproportionately affects long-duration growth stocks (e.g., technology) whose value is more weighted to distant cash flows.

- Increased Cost of Capital: Higher borrowing costs can reduce corporate investment, share buybacks, and margin expansion, potentially slowing earnings growth.

- Economic Slowdown Risk: The primary intent of tightening is to moderate economic activity. Rising recession risks can lead to downward revisions in earnings forecasts.

- Sector Rotation: Performance often rotates from rate-sensitive growth sectors to sectors that benefit from higher rates (e.g., financials, via improved net interest margins) or are less cyclical.

During an Easing Cycle (Falling Rates):

- Valuation Support: Lower discount rates boost the present value of future earnings, providing a tailwind for equity valuations, especially for growth stocks.

- Reduced Cost of Capital: Cheaper borrowing can fuel corporate expansion, M&A, and buybacks.

- Economic Stimulus Intent: Rate cuts are designed to support economic activity, potentially improving the outlook for corporate revenues and profits.

- The “Fed Put” Sentiment: Markets may interpret aggressive easing as a strong backstop from the central bank, boosting investor confidence and risk appetite.

Critical Nuance: The reason for the cycle matters. Rate hikes driven by strong growth may initially be positive for cyclical earnings, while hikes driven solely by runaway inflation can be negative from the outset. The market’s focus is often on the expected terminal rate and the pace of change.

Part 3: The Transmission to Forex Markets

For currency markets, the relative policy cycle between two countries is paramount, driving capital flows.

The Interest Rate Differential Channel:

- Tightening Relative to Peers: If the U.S. Federal Reserve is hiking rates while the European Central Bank is on hold or cutting, the interest rate differential between USD and EUR assets widens. This attracts global capital into higher-yielding USD assets, increasing demand for dollars and causing USD appreciation against the EUR.

- Easing Relative to Peers: If a central bank embarks on a more aggressive cutting cycle than its counterparts, its currency typically depreciates as the yield advantage erodes.

The Policy Divergence Trade:

Forex markets are intensely focused on policy divergence. The currency of the central bank that is perceived to be “ahead” in its tightening cycle or “behind” in its easing cycle will often strengthen.

Real Interest Rates and Forward Guidance:

- Real Rates Matter: The market focuses on real interest rates (nominal rate minus inflation). A country raising rates while controlling inflation (rising real rates) will see stronger currency demand than one raising rates merely to chase high inflation.

- Anticipation is Key: The market’s reaction is often strongest when a new cycle is anticipated or announced (the “pivot”). The actual implementation of well-telegraphed rate moves may have a diminished effect, as it is already “priced in.”

Risk Sentiment Overlay:

- In a broad “risk-off” environment, the normal interest rate dynamic can be temporarily overridden. Investors may flock to traditional safe-haven currencies (USD, JPY, CHF) even if their central banks have low rates, seeking liquidity and stability over yield.

Conclusion: The Dominant Macro Backdrop

Interest rate and central bank policy cycles create the dominant macroeconomic backdrop for financial markets. They are not mere technical adjustments but represent the core lever through which authorities manage the trade-off between growth and inflation.

For stock markets, the cycle influences the twin pillars of valuation and earnings through the cost of capital and the economic growth outlook. For forex markets, it dictates capital flows through shifting yield differentials and policy divergence.

The profound impact stems from their pervasiveness (affecting all assets), their predictable sequencing (monitoring, guidance, action, pause, pivot), and the forward-looking nature of markets, which constantly attempt to price in the entire future path of rates. Understanding these cycles is fundamental to interpreting market movements not as isolated events, but as reactions to the changing price of time and money set by the world’s powerful financial institutions.

2 comments