Can a Currency Survive War, Government Failure, or Revolution?

Currencies are more than paper or digital entries—they represent trust in a government’s stability, economic management, and ability to maintain value. In times of war, government collapse, or revolution, this trust often erodes, leading to severe devaluation, hyperinflation, or complete replacement. While some currencies endure through reforms or international support, many do not “survive” in their original form or value. Survival depends on factors like the crisis’s duration, external aid, resource backing (e.g., oil or gold reserves), and post-crisis governance.

Historically, extreme events disrupt money supply (e.g., printing to fund wars), cause capital flight, and trigger shortages, accelerating inflation. Governments may impose controls like price freezes or capital restrictions, but these often fail, leading to black markets or using foreign currencies. Below, we explore this through key historical examples, including how ordinary people and businesses navigated the turmoil. This is not Financial advice and not financial prediction, just and opinion.

Understanding the Mechanisms

War often requires massive spending, leading governments to print money unchecked, as seen in many conflicts. Government failure—through corruption, mismanagement, or collapse—undermines fiscal discipline, causing hyperinflation (monthly inflation over 50%). Revolutions disrupt institutions, creating parallel economies or new currencies.

In such scenarios, currencies rarely “survive” unscathed:

- Short-term survival: Possible with foreign reserves or aid, but value plummets.

- Long-term: Often requires redenomination (e.g., removing zeros) or adoption of a new currency.

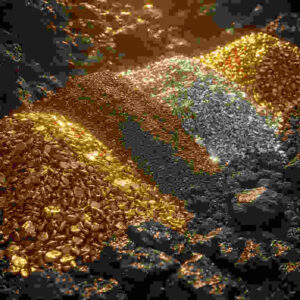

- Effects: Hyperinflation renders savings worthless, forcing barter or alternative stores of value like gold, livestock, or foreign cash.

People cope by hoarding goods, using black markets, or emigrating. Businesses face supply chain breaks, switching to barter, foreign invoicing, or shutdowns.

Historical Examples

1. Weimar Republic, Germany (Post-World War I Hyperinflation, 1919–1923)

After Germany’s defeat in World War I, the Treaty of Versailles imposed massive reparations, crippling the economy. The government, facing strikes and occupation of the Ruhr industrial region, printed Papiermark notes to pay debts and workers, igniting hyperinflation. By November 1923, inflation peaked at 29,500% monthly, with one U.S. dollar equaling 4.2 trillion marks.

The currency did not survive: The Papiermark became worthless, used as wallpaper or fuel. In 1923, the Rentenmark (backed by land and industrial assets) replaced it, stabilizing via a 1:1 trillion exchange, followed by the Reichsmark in 1924.

How People and Businesses Coped:

Ordinary Germans bartered goods like food or cigarettes, as cash lost value hourly—workers were paid twice daily to buy essentials before prices rose. Wheelbarrows of money were needed for bread; some burned notes for heat.

Businesses halted production due to unpredictable costs, switching to foreign currencies (e.g., U.S. dollars) for trade or indexing wages to gold. Black markets thrived, and savings evaporated, fueling social unrest and the rise of extremism.

2. Zimbabwe (Hyperinflation Under Robert Mugabe, 2007–2009)

It is said that Zimbabwe’s crisis is said to be stemmed from land reforms and economic mismanagement. War veterans’ payouts and involvement in the Congo War drained reserves, leading to excessive money printing. By 2008, inflation hit 79.6 billion percent monthly, rendering the Zimbabwean dollar (ZWD) worthless.

The currency collapsed: Trillion-dollar notes were issued, but by 2009, the government suspended the ZWD, adopting a multi-currency system (primarily U.S. dollars and South African rand). A new Zimbabwean dollar was reintroduced in 2019 but remains volatile.

How People and Businesses Coped:

It is said that citizens resorted to barter—trading chickens for medical care or fuel for food—and used foreign currencies. Hyperinflation wiped out pensions; people carried bags of cash for basics, but shops often refused local money.

Many businesses dollarized operations, importing goods with hard currency or closing due to shortages. Informal economies boomed, with remittances from abroad sustaining families. Unemployment soared to 80%, leading to mass emigration.

3. Venezuela (Bolívar Crisis Amid Political Turmoil, 2013–Ongoing)

For decade, Venezuela’s oil-dependent economy crumbled due to falling prices and U.S. sanctions. Hyperinflation began in 2016, peaking at over 1 million percent in 2018, devaluing the bolívar soberano (introduced in 2018 after the bolívar fuerte).

The currency persists but in a diminished state: Multiple redenominations (removing zeros) occurred, and partial dollarization was allowed in 2019. As of 2025, the bolívar is still legal tender, but U.S. dollars dominate daily transactions.

How People and Businesses Coped:

Venezuelans hoarded dollars or cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin for stability, using apps for remittances. Barter networks emerged—trading haircuts for food—and informal market exchange rates dictated prices. Businesses invoiced in dollars to hedge, imported via Colombia, or shut down amid shortages.

4. Confederate States of America (Civil War Currency Collapse, 1861–1865)

During the American Civil War, the Confederacy issued its own dollar to fund the war effort against the Union. Lacking gold reserves and industrial base, it relied on printing, leading to rapid inflation—over 9,000% by war’s end.

The currency failed: With the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865, Confederate notes became worthless souvenirs.

How People and Businesses Coped:

Southerners bartered cotton or tobacco, using Union greenbacks when possible (despite bans). Blockades caused shortages, forcing improvisation like using salt as currency. Businesses smuggled goods or operated on credit, but inflation eroded contracts. Post-war Reconstruction integrated the South back into the U.S. dollar system.

Broader Lessons and Survival Factors

Currencies can “survive” if crises are short or managed with reforms (e.g., introducing backed currencies). However, prolonged war or failure often leads to collapse, as trust evaporates. People and businesses adapt through informal systems—barter, foreign money, or migration—but at great human cost, including poverty and instability. These examples show resilience in chaos, but underscore the fragility of fiat systems without proper governance.

2 comments