Central Banking History and What it is : From Ancient to Modern

The concept of a central bank—a public institution tasked with managing a state’s currency, money supply, and interest rates—is a cornerstone of modern economics. However, its origins are deeply rooted in ancient practices of money lending, state finance, and the custodianship of value. The journey from the grain banks of Mesopotamia to the algorithmic monetary policy of the 21st century reflects the evolving relationship between state power, economic stability, and the trust required for complex financial systems. This historical survey traces the key developmental phases of the institutions that would become today’s central banks. This article is not investment advice or price predictions, only some information in the past gathered and explained.

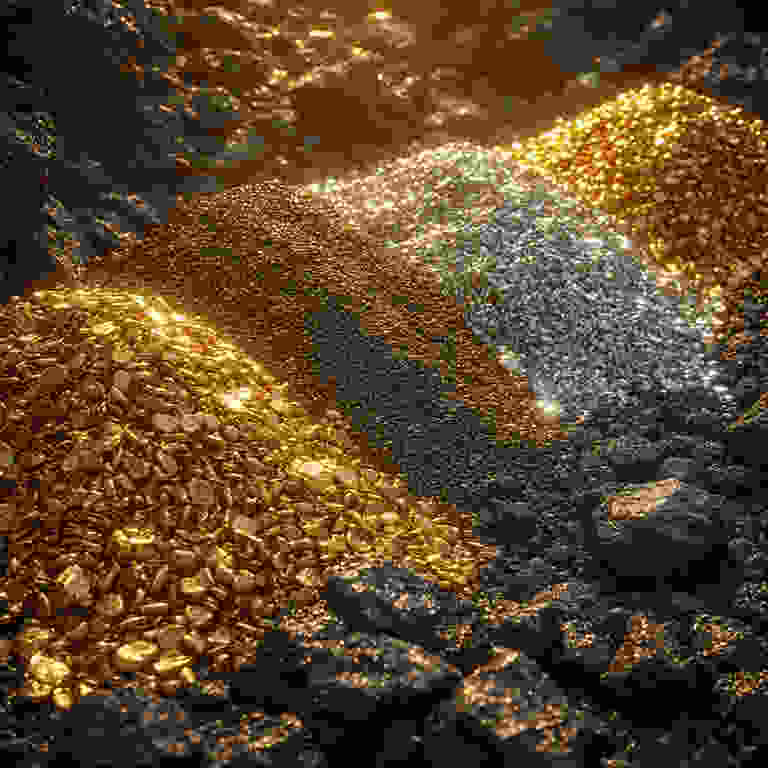

Part I: Ancient and Medieval Precursors (3000 BCE – 1500 CE)

Long before the term “central bank” existed, proto-banking functions were performed by temples, palaces, and early merchant banks.

1. Sacred Storehouses: Temples as the First Banks

- Ancient Mesopotamia & Egypt (c. 3000 BCE): Temples and royal palaces served as secure repositories for grain, precious metals, and other commodities. They acted as lenders to farmers and traders, issuing grain loans and precious metal receipts that could circulate as a form of early money. The Temple of Uruk in Sumer and state granaries in Pharaonic Egypt are prime examples. Their authority was derived from religious and royal power, establishing an early link between monetary trust and sovereign or divine authority.

2. The Rise of Merchant Banking

- Medieval Europe & Islamic World (c. 1000–1500 CE): As trade revived, private merchant banks (like the Medici Bank in 15th-century Florence) emerged. They dealt in bills of exchange, provided loans to sovereigns, and facilitated international trade. Key financial innovations like double-entry bookkeeping emerged here. While private, these banks sometimes performed quasi-public functions, but their failures (often due to sovereign defaults) highlighted the risks of intertwining private profit with public finance.

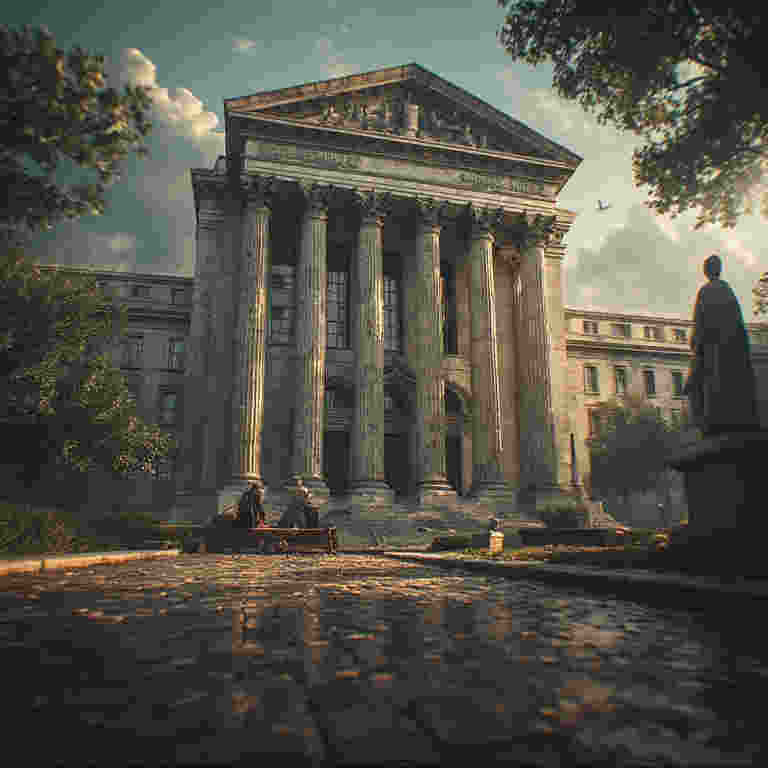

Part II: The First True Central Banks (1600–1800)

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the establishment of institutions with clearer central banking mandates, often born from wartime fiscal necessity.

1. Sveriges Riksbank (1668): The First Official Central Bank

- Founded from the ruins of Stockholms Banco (which had issued Europe’s first banknotes in 1661, leading to a collapse), the Riksbank was chartered by the Swedish parliament. It was the first European bank to be under explicit parliamentary control, not the monarch, and began issuing standardized banknotes. Its founding marks the recognized beginning of central banking as a public, note-issuing monopoly.

2. Bank of England (1694): The Archetypal Model

- Created by a group of private subscribers in exchange for a £1.2 million loan to King William III to fund a war with France. In return, it received a royal charter and the right to issue banknotes backed by its holdings of government debt. It gradually evolved its core functions:

- Banker to the Government: Managing public debt.

- Banker to Banks: Other banks held accounts with it, making it a “bankers’ bank.”

- Monopoly on Note Issue: By the 19th century, it had a monopoly on banknote issuance in England and Wales.

- The Bank of England became the model for central banking, demonstrating how such an institution could stabilize public finance and, eventually, the banking system itself.

3. The Banque de France (1800): Stabilization after Revolution

- Napoleon Bonaparte established the Banque de France to stabilize the French currency and economy after the hyperinflation of the assignats during the Revolution. Its mandate was to issue sound banknotes and support state credit, cementing the idea of a central bank as a guardian of monetary stability.

Part III: The Classical Gold Standard Era (1870–1914)

This period saw the formalization of the central bank’s primary role: defender of the currency’s convertibility.

- The “Rules of the Game”: Under the international Gold Standard, a central bank’s core duty was to maintain the fixed parity of its currency with gold. It would raise interest rates to attract gold inflows during a deficit and lower them during a surplus.

- Lender of Last Resort Theory: Walter Bagehot, in his 1873 book Lombard Street, formalized this crucial doctrine. In a financial panic, a central bank should lend freely to solvent institutions, against good collateral, but at a penalty rate. This established the central bank as the ultimate guarantor of systemic liquidity.

- Proliferation: Inspired by the British model, many nations established central banks during this era (e.g., Bank of Japan, 1882; Swiss National Bank, 1907).

Part IV: Crisis, Fiat Money, and Active Management (1914–1970)

World wars and economic catastrophe forced a radical transformation.

- World Wars and the End of Gold Convertibility: To finance total war, central banks suspended gold convertibility, effectively placing the system on a “fiat” basis where currency value was based on government decree rather than metal backing.

- The Great Depression and Policy Failure: Many central banks, clinging to gold standard orthodoxy, raised interest rates to defend gold reserves precisely when economies needed liquidity, exacerbating deflation and bank failures. This was seen as a catastrophic policy failure.

- The Bretton Woods System (1944–1971): A new semi-fixed system was created, with the US dollar (convertible to gold) as the anchor. Other central banks pegged their currencies to the dollar. This made the U.S. Federal Reserve (founded 1913) the world’s de facto central bank. Central banks now actively managed this fixed-rate system.

Part V: The Modern Era of Inflation Targeting and Independence (1971–Present)

The collapse of Bretton Woods ushered in the current framework.

- The Fiat Standard (Post-1971): With the final break from gold, central banks gained full control over domestic monetary policy but also the sole responsibility for controlling inflation.

- The Great Inflation and the Rise of Independence: The high inflation of the 1970s was blamed on political pressure on central banks to finance government spending and stimulate growth at the cost of price stability. The solution, pioneered by the Bundesbank and later the Fed under Paul Volcker, was operational independence—granting central banks a mandate (primarily price stability) and the freedom to set interest rates without political interference.

- Inflation Targeting: From the 1990s, many central banks (e.g., Bank of England, Bank of Canada) formally adopted explicit, public inflation targets (e.g., 2%), enhancing transparency and accountability.

- The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and Beyond: Central banks deployed unprecedented tools: slashing rates to zero (and even negative), and engaging in Quantitative Easing (QE)—large-scale purchases of government and other bonds to inject liquidity. Their role expanded to include macroprudential regulation—monitoring and mitigating systemic risks across the entire financial system.

- The Digital Frontier: Today, central banks globally are researching and developing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), potentially the next evolution in state-backed money.

Conclusion: From Storehouse to System Steward

The history of central banking is a story of institutional adaptation. Its evolution mirrors the progression of the economy itself: from agrarian storehouses to merchant capitalism, to industrial finance, to a globalized, digitized financial complex.

The core thread has been the search for monetary stability—whether defined by a fixed weight of gold, a pegged exchange rate, or a low inflation target. The central bank has transformed from a financier of the sovereign, to a guardian of the gold peg, and finally to an independent, technocratic manager of the fiat monetary system and a lender of last resort in times of crisis. Its history suggests its future will continue to be defined by its response to the next great economic challenge, be it digital disruption, climate change, or new forms of financial instability.

2 comments