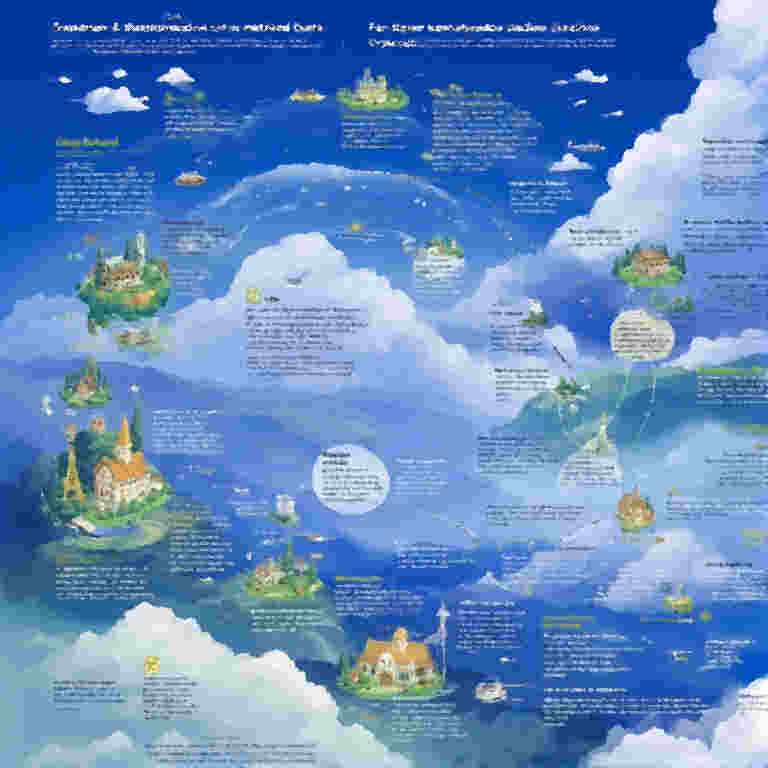

History of Money and Currency : 40,000 Years of Human Exchange

Money is so ordinary today that we rarely stop to ask what it really is. At its core, money is simply the thing we all agree to accept in exchange for goods, services, and debts. That agreement has taken thousands of different forms across the ages, and its history is one of the clearest windows into how human civilization itself evolved. This article is not for financial advice but for informative purpose only.

Before Money: Gift, Barter, and Social Debt (40,000 BCE – 3000 BCE)

The oldest evidence of systematic exchange comes from Ice Age Europe and Australia around 40,000 years ago. Archaeological sites show that people traded rare seashells, obsidian, and red ochre over hundreds of kilometres. These items were not food or tools—they were prestige objects used to create alliances, pay bride-prices, or settle feuds. Anthropologists call this “primitive valuables” or “social currency.”

In Mesopotamia around 7000 BCE, clay tokens shaped like sheep, jars of oil, or measures of grain were used to keep track of debts inside temple storehouses. By 3500 BCE these tokens were sealed inside clay envelopes (the first “contracts”), and eventually people began pressing the symbols directly onto wet clay tablets—the birth of writing itself was partly an accounting technology.

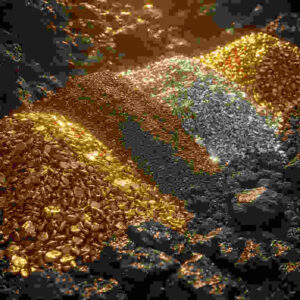

The First So-called Money: Commodity Money (3000 BCE – 700 BCE)

Around 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, silver began to be weighed on balances and used as a unit of account. The basic unit was the shekel—literally “a weight” of about 8.3 grams of silver. Temples and palaces kept standard weights and guaranteed purity, so a shekel of silver from Ur was accepted in Lagash.

In ancient Egypt (c. 2600 BCE), grain stored in state granaries functioned as money. Workers on the pyramids were sometimes paid in bread and beer, and tax records show grain being used to settle almost every kind of debt.

The first metal coins appeared around 650 BCE in the kingdom of Lydia (modern western Turkey). Made of electrum (a natural gold-silver alloy), these bean-shaped pieces carried the royal lion stamp as a guarantee of weight and purity. Within a century, pure gold and silver coins were being struck in Greece, Persia, India, and China almost simultaneously—an astonishing case of parallel invention.

Classical and Medieval Money (500 BCE – 1500 CE)

- Greek city-states issued beautiful silver coins (Athens’ owl tetradrachm became the “dollar” of the ancient Mediterranean).

- The Roman aureus (gold) and denarius (silver) circulated from Britain to Syria.

- In China, round bronze “cash” coins with square holes (so they could be strung together) were used from 221 BCE until the early 20th century—probably the longest-lived currency design in history.

- During the European Middle Ages, silver penny coins were so scarce that people often cut them into halves and quarters (“halfpennies” and “fourthings”).

From the 7th century CE, the Islamic world introduced the gold dinar and silver dirham, whose weights were copied by Christian kingdoms and which remained stable for centuries.

The Great Innovation: Paper Money (7th century CE – 17th century)

China again led the way. By the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) merchants were depositing metal cash with wholesalers and receiving paper “deposit certificates.” During the Song dynasty (11th–13th century), the government issued the world’s first true paper money—Jiaozi and later Huizi—because there was not enough bronze or silver to keep up with trade.

By the 13th century, Marco Polo marvelled at Kublai Khan’s paper money backed only by the threat of death for refusal. Europe would not see widespread paper money until the 17th century (Sweden’s Stockholms Banco in 1661 and the Bank of England in 1694).

The Gold Standard Era (1816 – 1933)

In 1816, Britain officially put the pound sterling on the gold standard: any paper note could (in principle) be exchanged at the Bank of England for a fixed weight of gold. Most major countries followed by the 1870s. For the first time in history, the currencies of distant nations were linked by a single metallic standard.

This era created unprecedented price stability across borders but also rigidity. Countries that ran out of gold were forced into brutal deflation. The system finally shattered during the Great Depression when nation after nation abandoned gold convertibility.

Fiat Money and the Modern Age (1944 – today)

The 1944 Bretton Woods agreement tied most currencies to the U.S. dollar, and the dollar itself to gold at $35 an ounce. When the United States suspended gold convertibility in 1971 (the “Nixon shock”), the world entered the pure fiat era: money backed only by government decree and public confidence.

Since then, every major currency—from the dollar, euro, and yen to the yuan and rupee—has been fiat. Central banks can create or destroy it at will, giving them powerful tools to fight recessions but also the temptation to overdo it (hyperinflation in Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, Venezuela).

Digital and Cryptocurrency (2009 – present)

In 2009, an anonymous person or group using the name Satoshi Nakamoto released Bitcoin—a first prime so-called cryptocurrency, a digital bearer asset that claimed to have no government or bank controls. Some people (not everyone) think that for the first time since the abandonment of the gold standard, this is a form of money exists that is both scarce (only 21 million will ever exist) and not dependent on any central authority. Many people however, see this as a digital asset, just like digitalized or digital-based form of gold or silver. Many people see it as speculative things. Many see it as part of blockchain technological development that could be use on other purpose, rather than currency.

Whether cryptocurrencies will one day replace fiat currencies, coexist with them, or remain niche assets is still unknown. What is certain is that the story of money has never stopped evolving.

The Thread That Connects 40,000 Years

From shells to silver, coins to paper, gold to fiat, and now to code, every form of money has rested on the same foundation: collective trust. As long as humans trade, argue, love, and fight, we will keep inventing new ways to keep score. The objects change; the need for a shared measuring stick of value never does.

2 comments